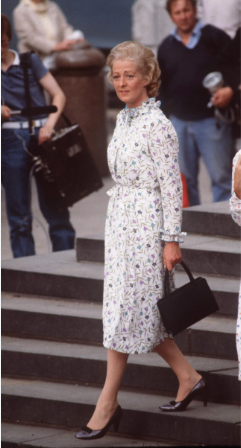

Born Frances Roche to parents with royal links, this society figure suffered in her unhappy marriages under an unwanted spotlight

Frances Shand Kydd always had royal links – even before she gave birth to the baby girl who would one day become Diana, Princess of Wales. Much like her daughter, the former Viscountess Althorp was fully ensconced in the upper echelons of high society, but found her life restrictive and often difficult, persecuted as she was by the demands upon her to produce a son and heir.

Born Frances Ruth Roche at Park House (on the royal estate at Sandringham, no less) in 1936, the future Viscountess shared her birthday with the death of George V. Her father, Maurice Roche, was 4th Baron Fermoy and a great friend of George VI; her mother, meanwhile, was a confidante and lady-in-waiting to Queen Elizabeth, later the Queen Mother. Styled an Honourable as the daughter of a baron, Frances was educated at Downham School in Esxen, and had barely graduated when she became engaged to Edward John Spencer, Viscount Althorp.

Aged just 18, Frances married the then 30-year-old ‘Johnnie’ at Westminster Abbey, one of the youngest ever brides to wed at the historic venue. But far from making a happy couple, Frances and Johnnie were deeply unhappy in their union. author of The Palace Papers, Frances soon discovered her outwardly polite and friendly husband to be an abusive bully who drank excessively, and demanded a son and heir from his new wife.

A boy would continue the Spencer name and inherit the family fortune, although this proved to be quite a challenge for the couple to fulfil. Frances gave birth to their first child, Lady Sarah McCorquodale, in 1955, and went on to have another daughter, Lady Jane Fellowes, in 1957. ‘In order to produce a male heir, he made Frances go through six pregnancies in nine years, of which only four were carried to term, and he resented her having any independent life,’ wrote Brown in her inside story.

Frances did then give birth to a baby boy, named John – who sadly passed away hours after birth. Viscount Spencer is said to have forbidden Frances from seeing the baby, who she would discover years later had been born with ‘extensive malformation’, an experience which traumatised her. ‘She struggled from the bed and banged frantically on the locked doors of the nursery to which he had been snatched away,’ Brown wrote. Frances herself recalled: ‘My baby was snatched away from me and I never saw his face. Not in life. Not in death. No one ever mentioned what had happened.’

A year and a half later, Diana was born, but there was a great sense of disappointment in the Spencer family that the new baby was not the longed-for male heir. Indeed, the couple hadn’t even thought of a girl’s name for the arrival, and it took a week for them to settle on Diana. Older relatives asked,according to royal writer Andrew Morton , ‘what was wrong with the mother’ – and, at just 23 years old, Frances was subjected to ‘intimate tests’ at clinics on London’s Harley Street to diagnose the so-called ‘problem’, which she found ‘humiliating and unjust’.

Eventually, Frances did give Johnnie his much-desired male heir: in 1964, Charles, now the ninth Eart Spencer, was born. Referring to his parents’ struggles in Morton’s 1992 book, Diana: Her True Story – In Her Own Words, Charles called it a ‘dreadful time’ and ‘probably the root of their divorce, because I don’t think they ever got over [the strain]’.

Indeed, just three years after Charles’ birth, Frances left her husband to be with Peter Shand Kydd, a wallpaper tycoon whom she had met the year before; two years later in 1969, she and John divorced. She earned the nickname ‘the Bolter’ and began a blazing custody battle with John, during which her own mother testified against her; John was subsequently awarded sole custody of their children.

Our father was a quiet and constant source of love, but our mother wasn’t cut out for maternity. Not her fault, she couldn’t do it. She was in love with someone else — infatuated, really,’ Charles told the Sunday Times in 2020. In the mid-1970s, John moved the family to Althorp , the Spencer family estate in Nortthamptonshire , while Frances married Shand Kydd, moving with him to the Scottish Isle of Seil, close to Oban, where she opened a gift shop and appeared content to live a life of relative obscurity.

However, Diana’s marriage to the Prince of Wales in 1981 shattered that privacy, making her a target in the press. When, after 19 years, her husband left her for a younger woman, Frances Blamed this sudden limelight: ‘I think the pressure of it all was overwhelming and, finally, impossible for Peter. They didn’t want him. They wanted me. I became Diana’s mum, and not his wife.’

Following her second divorce, Frances converted to Catholicism in 1994, immersing herself in good works and making annual pilgrimages to Lourdes as a carer for disabled people. She organised fundraising for the bereaved families of the Lockerbie air crash, and, as patron of the Mallaig and North-West Fishermen’s Association, subscribed to Scottish Fishing Monthly to keep up with the issues.

Frances was devastated by Diana’s death in 1997, especially as the two had not been able to patch over a rift cased by a magazine interview she had given, four months earlier, which disclosed personal details about her daughter. The interview raised £30,000 towards the building of a Catholic prayer house on Iona, but the damage was done – and Diana was said to have returned many of her mother’s letters unopened.

Haunted by the fact that she was never able to reconcile with her daughter, Frances went out of her way to support other mothers whose children had died tragically. There was some small consolation, however: that she remained executor of Diana’s will, and had been assigned special responsibility for overseeing the upbringing of Princes William and Harry. Frances spent her last years in solitude on Seil, devoting herself to charity work, before she died at the age of 68 in June 2004. Her small funeral in Oban was attended by William, who gave a touching reading, and Harry – a gesture that showed, despite their estrangement, a kinship between Frances Shand Kydd and her beloved daughter, until the end.